The Lusitanians and Illyrians were almost contemporary (approx. IV cent. BC) European peoples who shared the 40th parallel, embracing the two extremes of Southern Europe – a Luso-Illyrian project.

The Lusitanians and Illyrians were almost contemporary (approx. IV cent. BC) European peoples who shared the 40th parallel, embracing the two extremes of Southern Europe – a Luso-Illyrian project.

Faced with the undeniable signs that the new millennium is still dominated by suffering, conflict and inequality, a new objective emerges – towards Human Development.

Origins

Although the borders of Lusitania do not coincide exactly with those of today’s Portugal, the people who lived there are one of the ethnological foundations of the centre and south of Portugal people, and also those of the Spanish Extremadura.

Many of the ancient people who entered the Iberian Peninsula left traces of commercial contact and cultural influence in the Lusitania territory. In particular, the Roman occupation and the invasions of Visigoths and the Arabs left clearly evident and revealing vestiges revealing a deeper assimilation. Some ancient historians refer to the gold of Lusitania, wealth that, along with silver, is witnessed today in Portugal by the frequent finds of jewellery made with those metals – necklaces, bracelets, earrings, etc. Abundant copper was extracted from mines in the south. Lead was found, according to Pliny, in the Lusitanian City of Medubriga Plumbaria, which was named thus due to the local abundance of this mineral.

For administrative purposes, the Romans divided it into three conventus, with a total of 46 cities, 5 Roman colonies, amongst which two correspond to Beja (Pax Julia) and Santarém (Scalabis); another of Roman descent, Olissipo (Lisbon); three were under Roman protection – Ebora, Myrtilis and Salacia (Évora, Mértola e Alcácer do Sal) and finally 37 were classified as stipends, standing out amongst them are Aeminium (Coimbra), Balsa (Tavira) and Miróbriga (Santiago do Cacém).

Some of these communities have been found with precision: Ossonoba (Faro), Cetóbriga (Tróia de Setúbal), Collippo (Leiria), Arabriga (Alenquer).

The administrative link with Rome terminated in 411 when the emperor Honorius, after a prolonged period of civil war, established a pact with the Alanos and granted Lusitania to them. Two years later, however, the Visigoths expelled the Alanos, initiating the dominion of Lusitania south of the Tagus River, while to the north the Suevos kingdom continued, with Braga as its capital.

Who were the Lusitanians?

The Lusitanians are usually seen as one of the ancestors of the Portuguese of central and southern Portugal and Extremadura. They were celtiberian people who lived in the western part of the Iberian Peninsula. Originally, they were a single tribe that lived between the Douro and Tagus rivers or the Tagus and Guadiana rivers. To the north of the Douro they were constrained by the Galicians and Asturians – who made up the majority of the population of northern Portugal – in the Roman province of Galécia, to the south by the Baetica and to the west by the Celtiberians in the more central area of Hispania Tarraconense.

The most notable Lusitanian figure was Viriato, one of the leaders in the fight against the Romans.

Source: www.wikipedia.org

Origin and the Historic Territory of the Illyrians

In Albanian, Iliria – “land of the free”

In Albanian, Iliria – “land of the free”

In Greek, Ἰλλυρία

In Latin, Illyricum

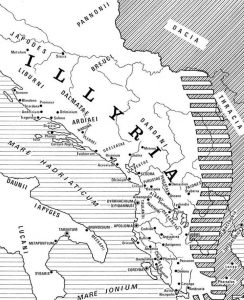

According to the available historical sources, the term “Illyrian / Illyria” has a historical–geographic significance which is, on occasion, distinctive. According to recent studies, based not only on written sources but also on archaeological and linguistic discoveries, it appears that the historical territory of the Illyrians covered the whole western part of the Balkan Peninsula, from the source of the Morava and Vardar rivers in the East, to the coast on the Adriatic Sea and the Ionian in the west, and from the Sava river in the north to the Ambracia Gulf in the South, that is, to the border of Ancient Greece. The capital of the Kingdom of Illyria is the current Albanian city of Shkodra.

The Illyrians spoke a language that differs from the languages of other ancient peoples of the Balkan Peninsula. It was a specific Indo-European language with some similarities to other languages of the time.

The Greek and Latin languages, which entered the Illyria kingdom as languages of culture and business and official administrative languages, where never assimilated by the people, who kept their mother tongue intact in their daily lives. Some elements of the original language of the Illyrians remain, such as around 1,000 names of people, gods, tribes and places, and some names of rivers, mountains and cities (e.g. Skodra, Lisi Dyrrahu, etc.) that continue to use these names today. Various scholars have also identified as Illyrian some words present in other languages, both ancient and current European languages, which were imported or inherited from the Illyrian language.

Culture

The Illyrian culture has characteristics that distinguish it from neighbouring Bronze Age cultures. It was a unique culture originating in the historic land of the Illyrians, strongly marked by the socio-economic development of this people and, without doubt, by its relationship with neighbouring ones.

The main aspects of this culture is overwhelmingly manifested in the achievements of the Illyrians in the area of socio-economic development, in their way of life and in their perception of the world around them, as well as in their reflections on that world in arts and in creativity in general. A territory with many regional socio-economics disparities, the Roman invasion contributed to the reduction in the differences in ethnographic characteristics of the Illyrians. An argument that is used to prove this Romanization is the adoption of Latin language as the official language at that time. However, the Latin language never succeeded in replacing the Illyrian language, particularly as the most expressive instrument in social and family relationships, not even in the cities where the Illyrians lived alongside Roman residents. The presence of the Albanian language in contemporary territories of southern Italy bears clear witness to the inefficient nature of the Romanization of a large part of this population.

The main aspects of this culture is overwhelmingly manifested in the achievements of the Illyrians in the area of socio-economic development, in their way of life and in their perception of the world around them, as well as in their reflections on that world in arts and in creativity in general. A territory with many regional socio-economics disparities, the Roman invasion contributed to the reduction in the differences in ethnographic characteristics of the Illyrians. An argument that is used to prove this Romanization is the adoption of Latin language as the official language at that time. However, the Latin language never succeeded in replacing the Illyrian language, particularly as the most expressive instrument in social and family relationships, not even in the cities where the Illyrians lived alongside Roman residents. The presence of the Albanian language in contemporary territories of southern Italy bears clear witness to the inefficient nature of the Romanization of a large part of this population.

Various scholars have used linguistic, archaeological and extra-archaeological evidence to argue that even after the Roman invasion, the Illyrians had neither disappeared nor been assimilated, but kept many elements of their material and spiritual culture, preserving a compact and stable population, and that the Illyrian Kingdom resisted Romanization more effectively in southern Illyria – lands that are now inhabited mainly by Albanians.